Why Is Genre Important In Writing

Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

Understanding the importance of genre in writing is the key to success. Get it wrong and it will cost us, as writers, a small fortune in book sales and advertising dollars. Get it right, and readers will tell their friends about us. Why? Because genre is all about reader expectations, and if a Story doesn't meet them, it's finished. Even the most beautiful turn of phrase can't save it.

Harsh, I know.

I learned that lesson the hard way. I got genre wrong and I lost a small fortune. I really don't want you to go through that. As an editor, and fellow writer, I want you and your Story to shine.

It was only when I began paying close attention to what Shawn Coyne had to say about genre, that things started to turn around for me. Trust me, genre matters more than you think. It affects every aspect of your Story. It will shape your characters. It will save you in the middle build. It will release your true creative potential. It will inform your marketing strategy. And most of all, it will enable you to tell a Story that readers enjoy. When that happens, they'll tell their friends about you.

You see, Steven Pressfield is right. In this business, Nobody Wants To Read Your Shit (or mine) unless you convince them they should. Nailing your genre is how you do that. Of course, genre is a huge topic and Shawn has talked about it for both fiction and non-fiction. In this article, I'll be primarily focusing on genre as it relates to fiction.

There was a time when I dove into writing projects with little more than a passing thought to genre. These days, I'm keenly aware of which genre I'm writing in. As a result, readers are recommending my work to their friends, and they're emailing me to ask when my next novel will be published.

And it's all thanks to Shawn, his concept of genre and his Story Grid Five-Leaf Genre Clover.

What does Genre mean?

We were readers before we were writers. Some of us are also literary scholars and hold English degrees and MFAs. While this experience helps to inform our writing, it means that we all have a different perception of genre in writing. We're used to looking at genre as a reader does, or as a scholar does. Now we have to look at it as a writer does.

Think of it this way. You're craving a hamburger – a half pound of thick, juicy, flame-broiled, prime beef topped with sharp cheddar and maple smoked bacon. You've been working out at the gym all week and watching your diet. It's Friday night, and you've earned your treat. You go to the best restaurant in town and ask for a burger. Twenty minutes later the waiter brings you a tofu burger. This is award-winning tofu, prepared by a top chef. The waiter assures you that it's delicious and although it may well be, it's not what you were expecting. It's not your idea of a burger. It's not what you were in the mood for and so you feel disappointed. You won't be recommending the restaurant because they didn't give you what you wanted.

As readers, we love science fiction and so when we become authors we want to write science fiction. Fair enough, but what kind of science fiction? There's a huge difference between Star Wars and Alien. We love the classics and want to write literary Stories that explore a character's inner growth. Okay, but what's causing the inner growth? Are the characters trying to survive on a desert island (Lord of the Flies, William Golding)? Are they watching a legal trial about racial relations (To Kill A Mockingbird, Harper Lee)?

Life would be so much easier if we all had the same menu of Story types to choose from. Since we don't, as writers we have to think carefully about our genre choice. We have to look at it from different angles. Some books are fairly straightforward; people know that Agatha Christie is mystery although in bookstores you'll find it in both the mystery and literature sections. Other books, like Outlander, are a complete conundrum. Even Diana Gabaldon didn't know what to call it when she started.

This begs the question, if the genre of Outlander is unclear, why is it such a roaring commercial success? The answer is that at some point, everyone agreed to call it a historical romance. Its publication has since spawned the sub-genre of Scottish historical romance. There's a market for men in kilts.

The bottom line is this: genre in writing refers to the kind of Story that is being told. It's about audience expectation. It's that simple. For a book to be successful the author, marketer and reader must all have the same understanding of what kind of Story is being told.

Choose Only One Genre

If Shawn has said it once, he's said it a thousand times. A writer must make a definite choice about which genre she's writing in.

Pick one. Only one.

This is non-negotiable.

Sometimes you can do this accurately at the beginning of a project. Other times, you might need to crank out a first draft before you figure it out. Both ways can work. The point is that you must make a choice. Unless we are crystal clear about what kind of book we want to write, we will get confused and lose our way in the middle build. If we're confused, the reader is confused.

"If you make the audience groan, I can tell you, it's hard to get [them] back. The first thing I want to know — in fact, the only thing I want to know — is, was it comprehensible? Did [the audience] follow the Story? If you put confusion into the mix, even the tiniest bit of confusion, the audience is going to be apprehensive. An audience needs to feel, when they sit down in that chair, that the storyteller has them by the hand and is leading them through the Story."

– Aaron Sorkin, Masterclass

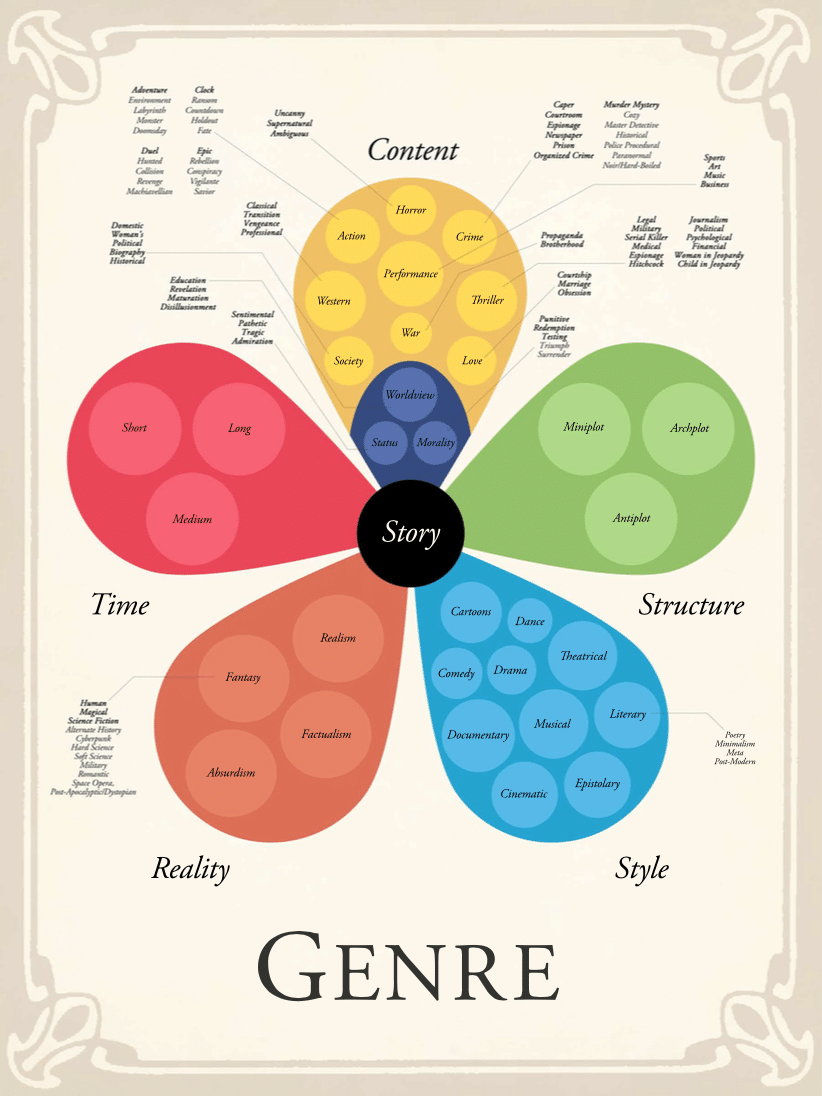

Enter, The Story Grid Five-Leaf Genre Clover

[download a copy of this clover graphic here]

Shawn spent 25 years grinding on this. He has already sweat blood so we don't have to. He listened to writers explain the Stories they wanted to tell. Then he figured out a way to categorize it and explain it to the art and marketing departments so they could target the book to the appropriate readership.

I see the Story Grid Five-Leaf Genre Clover as both a roadmap and a universal translator. If you take the time to figure out how it works, you'll come to appreciate its brilliance. And no, I'm not saying that because Shawn has to approve this article. I'm saying it because it got me out of a serious jam. More on that later.

The clover has five leaves; time, reality, style, structure and content (external and internal). Choosing a genre in writing means making a choice about each of these leaves. Here's what they all mean:

I think you'll agree that the time, style and structure leaves are fairly straightforward. (Note that the clover considers literary to be a style.) It's the reality and content leaves that can give us a headache. The beauty of this system is that any kind of Story we can conceive, can be mapped out using the clover. Even LitRPG, which is an evolving genre, has a home here. It's not listed on the diagram above, but it falls on the reality leaf under Fantasy > LitRPG.

Let's say we want to write a story about an astronaut who gets stranded on Mars (The Martian, Andy Weir). Since we started as readers, we call this science fiction. And it is. However as writers, we have to go deeper. If we don't, we'll get lost in the middle build and we won't deliver a Story that meets reader expectations. (I know I said that before, but it bears repeating.) We have to ask ourselves what our Story is really about? Yes, it's set on Mars. Science informs the Story, but it isn't the Story. What we're really writing about is survival in a harsh environment. If you look at the clover, you'll see that The Martian falls on the reality leaf under Fantasy > Science Fiction, and on the content leaf as Action > Adventure > Environmental.

Let's go even deeper.

The content leaf is divided into two sections; yellow and blue. The yellow contains what Shawn calls external content genres, and the blue are the internal content genres. You know all the conversations authors have about whether they write plot-driven or character-driven novels? What they're talking about is this content leaf. Plot-driven books fall into the external content genres (the yellow). Character-driven books fall into the internal content genres (the blue).

Stories do not have to contain both internal and external content genres, but they can. Horror, crime and action often don't have internal genres and that's the way we like it. Freddy Krueger (A Nightmare on Elm Street) doesn't change, nor does Jack Reacher (Lee Child's protagonist) or Ethan Hunt (Mission Impossible).

When Stories contain both internal and external genres, one of them must take priority. Otherwise your reader will get confused. He picked up your book expecting a spy thriller and got a spy who spends more time agonizing over his abusive childhood than solving the crime. You might have written an excellent book, but if it isn't what the reader expected, it will disappoint.

Shawn talks about the global genre — by that he means the content genre in writing that takes priority in the Story. For example, in A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens) the global genre is internal (Morality > Redemption) and the secondary genre is external (Horror > Supernatural). Pride and Prejudice (Jane Austen) also contains both genres however its global genre is external (Love Story > Courtship) and its secondary genre is internal (Worldview > Maturation).

Putting it All Together

Understanding genre in writing, and how the five leaves work together, is the key to success. Let's say you want to write a novel about a guy who has to kill a vampire before his wife also becomes a vampire (Dracula, Bram Stoker). Your choices from the genre clover would look like this:

Time: Long (because it's a novel, in fact at 162,000 words one could argue that it's too long)

Reality: Fantasy > Magical (because this is a fantastical world with dark magic, like mind control, that Dracula has mastered)

Style: Epistolary (because Dracula is written as a series of letters, journal entries, telegrams and newspaper articles)

Structure: Archplot (because it has one storyline that follows the hero's journey)

Content External (which in this case is the Global Genre): Horror > Supernatural (because vampires don't really exist no matter what Anne Rice would have you believe)

Content Internal: Status > Sentimental (because against absolutely incredible odds, Jonathan Harker transforms from a poor legal clerk to rich business owner and savior of the world)

The Clover Doesn't Work For My Story

Yes, it does. Go deeper. What Story are you really trying to tell? Think hard. Spend time on this. If you can't articulate it to yourself, you'll never be able to explain it to a reader. That means that your reader will never know if your Story is the one he wants to buy.

J.K. Rowling Didn't Use The Genre Clover

You're probably right. The same is likely true of Stephen King. They both started their writing careers in elementary school though, and spent twenty years writing non-starters before they hit their home runs. That option is available to you. Personally, I don't see the appeal. I suspect Neil Gaiman doesn't use it either. Instead, as a child he read every book in his school library and then every book in his public library. He also spent twenty years writing books that went nowhere.

I don't mean to be flippant. There is no one way to write a novel. There's no one way to do anything. Authors like Rowling, King and Gaiman have studied books so much, and for so long, that they have an intuitive sense of how to tell a Story that works. I talk to plenty of writers who want to argue with the Story Grid method, and that is their prerogative. Before you cast it aside though, I urge you to test it out. Apply it to your favorite books and movies. Pick a wide range of Stories and take the clover for a test drive. It's then that you will realize that your time is better spent innovating your chosen genre, rather than arguing with it.

Genre Has Obligatory Scenes and Conventions

Ignore this advice at your peril. This is the meat and potatoes part of genre. A reader chooses a book because she wants a particular kind of story. If she chooses a murder mystery, she expects to read a scene where the dead body is discovered. She also expects to find out who the murderer is. The North American version of The Killing didn't adhere to its obligatory scenes and conventions and fans went berserk.

Robert McKee cites the film Mike's Murder as another example of a Story that missed the mark with respect to genre. It was marketed as a murder mystery but "the film, however, is in another genre, and for over an hour the audience sat wondering, "Who the hell dies in this movie?" (Story, page 90)

Mea Culpa

"You've got to learn from the audience. The difficulty is, it's going to cost you something. You've got to pay the price of putting up with their verdict. There is no higher court. You can't say, 'Wait a second audience, do you know how hard I worked?' They don't care, nor should they. They're asking, 'Did you do what I expected'?"

– David Mamet, Masterclass

Before I'd ever heard of Shawn Coyne or Story Grid, I also messed up on genre in writing. One day, I was lamenting to a writer friend that I couldn't find a romance novel I wanted to read. In her wisdom my friend, let's call her Anne, told me that if I couldn't find it I should write it. I knew nothing about the genre in writing so Anne — herself a USA Today Bestselling romance author — offered to show me around, introduce me to some folks, and explain how it all worked. She read drafts and suggested changes, most of which I ignored. I was not going to have my creativity stifled by such trivialities as the couple having a routine, or always meeting in the same café. I wanted my characters to have an arc, I am after all, a serious writer. (Talk about naiveté masquerading as sophistication. Oy.)

Anyhoo, I finished my book and sent it out into the world. The feedback I got was unanimous.

It was not what readers were expecting.

I'd given them tofu when they'd wanted beef. Lots of beef. Preferably raw.

I thought I'd give it some time, let it find its audience. Then I thought that if I just lowered the price a bit, or fiddled with the keyword search on Amazon then maybe … but, no. Sales remained flat. It was then that I reached my crisis moment. Should I abandon the book and start on the next one? Should I pump more time and money into its promotion? Should I swallow my pride and go back to basics? (This is a best bad choice crisis question, in case you're wondering.)

I went back to basics.

I had missed three very important conventions of a Love Story (external content genre). The first is that the couple must have rituals. For example, in Pride and Prejudice, Darcy and Elizabeth tease one another. The second and third relate specifically to romance novels as readers understand them. That is, there is no internal genre to speak of and there's no sub-plot. This is not a criticism, it's just the way it is. Take the film How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, for example. It's hugely popular, highly entertaining and has a rock solid Story structure. But the main characters, Andie and Ben, don't really change. Fans don't want them too, just like we don't want Jack Reacher to suddenly have a mid-life crisis. The only thing we care about is whether Andie and Ben get together. Their career goals are of zero interest.

I added in the rituals, but I didn't want to flatten my character arcs or remove my sub-plots. Those are the things that I'd been looking for in a Story and were the reasons I started the project in the first place.

Finally, I went to the clover and made decisions leaf by leaf. In doing so, I realized that although I had indeed written a Courtship Love Story, because of its strong internal genre and sub-plots, readers would recognize it as women's fiction. Remember above when I said that readers would consider The Martian to be a science fiction novel, but that as writers we have to go deeper and understand that it's really an action Story? This is the same idea. Once I made the switch, I developed a better marketing strategy and sales began to register.

I Don't Write Formulaic Novels

I'm very glad to hear that. The Story Grid view of genre in writing is not, in any way, a formula. It is however, a solid explanation of Story form. A professional understands the difference because she's learned it through study, trial and error.

Obligatory Scenes and Conventions Kill Creativity

I beg to differ. What obligatory scenes and conventions do is ensure you're telling a Story that works and that meets reader expectations. They must be in your Story, and the best part is that they present opportunities to be creative. Anyone can write a cliché. Clichés work, that's why they're used so often. Our challenge as professional writers is to present obligatory scenes and conventions in fresh new ways. We must level up and innovate the Hero At The Mercy Of The Villain scene, or the Lovers Meet scene. These are the places where we get to strut our stuff.

Genre in Writing: It is the Most Important Question

In fact, it's the key to success. Thanks to the Story Grid method, genre in writing is easy to define and understand, but it's still difficult to innovate, and innovation is a must.

Everything I write now falls into one clearly defined genre — that includes this article. Do you know which one? (I'll give you a hint: it's one of the four non-fiction genres Shawn talks about here and here.) Put your answer in the comments below and then download my Editor's Six Core Question Analysis.

To learn how to put storytelling theory into practice, subscribe to UP (the Un-Podcast) with Valerie Francis and Leslie Watts.

Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

Why Is Genre Important In Writing

Source: https://storygrid.com/importance-of-genre/

Posted by: martinposere88.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Why Is Genre Important In Writing"

Post a Comment